This is the latest in a series of articles looking at the grants industry. Today we look at tourism, leisure and the heritage industry.

____________

A few years ago Cneifiwr had visited what must have been one of the most depressing holiday destinations in Wales. The holiday complex is just outside a small village in Ceredigion, and at the time it specialised in holidays for the disabled, although it was open for general bookings as well.

The owner was a rather terse and deeply religious man who had been keen to provide holidays with a Christian ethos.

The chalets and cottages were shabby, damp and in as much need of a good clean as a lick of paint. In the centre of the complex was a cold and drab entertainment centre (a glorified shed), next to which stood a very large wooden cross which dominated the grounds. The idea was presumably that the holidaymakers would contemplate the meaning of life as they made their way to play tiddlywinks.

Tucked away to one side of the extensive grounds in an area which had become badly overgrown was an adventure playground with rope walks, turrets, ladders and slides. The whole thing had been cordoned off with red and white plastic tape and clearly had not been used for some time. Somewhere next to the enormous decaying wooden structure was a plaque to commemorate the official opening of the play ground which had been built with generous funding from some grant fund or other.

The adventure play ground was not that old and could have been tidied up and repaired, but it was clear from talking to the owner (a man originally from the Birmingham area) that he was not very keen on children, and the facility almost certainly ended up as firewood.

There was enough wood there to keep the fires going for several winters, so at least someone benefited. The complex was eventually sold to new owners.

And that raises a general question about many of the grants awarded to private businesses in this part of Wales - to what extent are they really contributing to the local economy and creating jobs?

Hot tubs

Last year this blog

noted that a holiday cottage business near Newcastle Emlyn had picked up £25,000 for two hot tubs and gazebos to protect them from the elements. You can buy a very good hot tub for around £6,000, and even if they are carefully maintained they will not last much more than ten years.

Looking after a hot tub is a time consuming business. You need to test the water and add chemicals several times a week, and the filters need to be cleaned at least twice a month because they get clogged up with hair and other detritus. How many holiday cottage owners go to all that trouble? Some perhaps, but not all. Why bother when it will be easy enough to get more grants in a few years time?

Those two hot tubs will probably cost the tax payer around £3,000 a year for 8 years, after which they will be scrapped.

As the owner of a holiday cottage business, the next step is to apply for a grant to install solar panels to heat the hot tubs. Another Carmarthenshire business was awarded £10,000 for solar panels for one holiday cottage and hot tub. If our friends near Newcastle Emlyn follow suit, which by all accounts they are very likely to do, we could be talking about £45,000, or somewhere in the region of £5,600 a year over the lifetime of the installation.

Hot tubs certainly make a holiday cottage more marketable, but do solar panels? And will these grants really translate into local jobs and more than £5,600 a year in spending in the wider local economy?

A short hop away from the luxury hot tubs and gazebos is another family-run holiday business near Drefach Felindre.

Dirt jumps

The Ceridwen Centre offers slightly alternative holidays with a green feel, tipis and composting toilets. In 2012 Meryl awarded it £23,000

for a wedding tipi, and she was pictured with the lucky

winners in a

press release last year.

A couple of months back Meryl handed the family another £24,630 for a "pump track, set of dirt jumps and technical skills area". The grant went to a company called West Wales Trails Ltd, a new business set up by a member of the family which owns Ceridwen, and the track will form a new attraction alongside the wedding tipi.

It brings the known total of grants for this outfit to £100,000 over the last few years, and there may be more.

Good luck to the owners, but how many local jobs have been created, and what is the benefit to the wider community? Trip Advisor, usually a good place to look if you are deciding to stay somewhere, has nothing to say about Ceridwen. You could be the first to provide a review, it says.

Peeping Tom

Just down the road from Ceridwen was another major recipient of grants at Penboyr. This was run as a charity called Harvest Trust specialising in holidays for deprived children.. The charity's founder is currently

languishing in prison after it was discovered that he had secretly filmed children naked, and the holiday complex was sold off at a knock down price.

Another private business not far away from the scene of all this grant action has just been awarded over £22,000 to install a wood burning stove,

solar panels, double glazing, landscape its garden, etc.

And

while the public is constantly baffled by the rules which govern

declarations of interest in council meetings, it seems that no

declarations of interest were necessary when Meryl dished out a £27,000

grant to her chum, Cllr Andrew James (Ind) for solar panels, a hot tub

and work on a toilet block at his caravan site last year. Meanwhile Towy Community Church, the beneficiary of so much council generosity, has just been given another £2,135, although we are not told what for.

Up there with Towy Community Church among the biggest recipients of grants and other public money in Carmarthenshire is Llanelly House.

Feasibility

By all accounts, Llanelly House is a good place to visit, and it has brightened up a corner of Llanelli, so no complaints there. It is owned and run by a charity called the Carmarthenshire

Heritage Regeneration Trust (CHRT), a charity which aims to save various

old buildings for posterity.

CHRT's most recent

accounts (to March 2013) boast that turnover rose again during the year,

although closer inspection shows that turnover was almost entirely

grant income, and expenditure exceeded income.

Strangely

there is no mention in the accounts of a funding crisis which caused

the Executive Board of Carmarthenshire County Council to approve an

interest-free loan of up to £250,000 to Llanelly House in 2012. Half of

that loan was supposed to be repaid in July 2013, but when the council's

chief executive was asked whether the loan had been repaid in a meeting

of the full council, he replied that the matter was not on the agenda.

We can probably take that as a "no".

CHRT

has noble aims, and there is no suggestion that its trustees are

spending money on themselves, but there are legitimate questions to be

asked about the way it operates.

In addition to

Llanelly House, CHRT has a number of other major projects on its books.

These include the restoration of Gelli Aur, the huge, rambling Victorian

mansion near Llandeilo. The recent history of this house is one of

appalling neglect, incompetence, greed and even fraud (see previous post

here).

Nothing seems to be happening to reverse the fortunes of Gelli Aur, and

the scale of the undertaking would dwarf what the trust has done in

Llanelli. It looks very much as though the charity's ambitions have far

outstripped its capacity to carry out its aims.

One of the properties on CHRT's books is the

Gatehouse of the former Penlan workhouse in Carmarthen. This is a modest

sized building, and the 2012-13 accounts report that the charity

received a grant of £11,500 from the Rural Development Programme, EU

funds managed by Carmarthenshire County Council.

The

grant was awarded so that the trust could commission a feasibility study

to determine whether the Gatehouse could be turned into holiday or

office accommodation.

£11,500 is a great deal of money

for a report of this kind on a modest property, and whoever wrote it did

very well out of the commission. Common sense and a

chat with a few local property specialists would have been enough to work out

that turning the building into holiday flats or offices was a

non-starter, and that appears to have been the conclusion of the £11,500

report because the Gatehouse is now up for sale, boarded up, as an

"exciting opportunity" for conversion into a family home.

Yours for less than £80,000.

So the future of the Gatehouse is once

again in doubt, and grant money which could have been spent on something

worthwhile has been wasted on a report which quite possibly only helped the author towards his or her next Range Rover.

A common feature of quite a few of the charities receiving grants in Carmarthenshire is that they are almost entirely dependent on grants for their income. Form filling rather than the arduous process of holding raffles, auctions, jumble sales, sponsored swims and rattling tins is how they get their money.

Major restoration projects will always be heavily dependent on

financial support from the lottery and other funds, but being obliged to

go out to the public and drum up support in local communities is surely

a healthy thing. No only does it get local people to buy in to

projects, but the likelihood is that charities will be much more careful

in how they spend money if they have local trustees who have raised

funds from the people around them.

Dylan was 'ere

Also in the big league when it comes to grants are some other privately owned businesses. One which has benefited from an enormous amount of free publicity this year is Browns Hotel in Laugharne, which was briefly a favoured drinking hole for Dylan Thomas.

Browns was owned for a while by actor Neil Morrissey who sold it to one of the Scarlets' directors, Nicholas Gallivan. It underwent a major refurbishment and re-opened in 2012, with the Welsh Government chipping in £230,000 and Cadw offering a further £62,500 according to a

BBC report.

The newly reopened Browns seems to be a success, and the grants have helped restore a Grade II building, create employment and give somewhere for visitors to go.

What is questionable however is whether quite so much public money should be handed to businesses which could well afford to invest from their own resources.

Meanwhile, Mr Gallivan and Nigel Short, chairman of the Scarlets, have been making quite a name for themselves in Bulgaria where they are involved, through a maze of Channel Islands and British Virgin Islands offshore companies, in a scheme to build a gigantic holiday complex and series of "eco villages" at Karadere Beach, one of the last remaining undeveloped parts of the Bulgarian coast.

A

Guardian piece with a description of the project can be found

here, while an investigative article on who some of the investors in this project are can be found

here

(in English after an short piece of text in Bulgarian). The scheme has

sparked major protests in the Bulgarian capital as well as in Karadere itself.

What we need, and not just in Carmarthenshire, is a much more open and rigorous audit process to establish whether the public is really getting value for money. If you receive £100,000 from public funds to invest in a private business, transparency should be a condition.

Did the money translate into more business, and what was the benefit to the local economy?

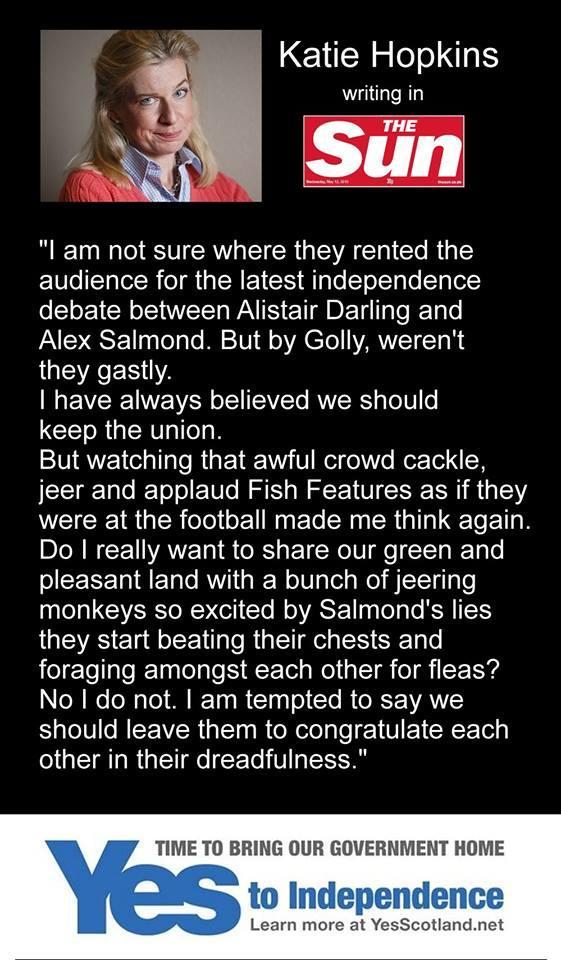

"I'm not sure where they rented the audience for the latest debate between Alastair Darling and Alex Salmond. But by Golly, weren't they ghastly.

"I'm not sure where they rented the audience for the latest debate between Alastair Darling and Alex Salmond. But by Golly, weren't they ghastly.